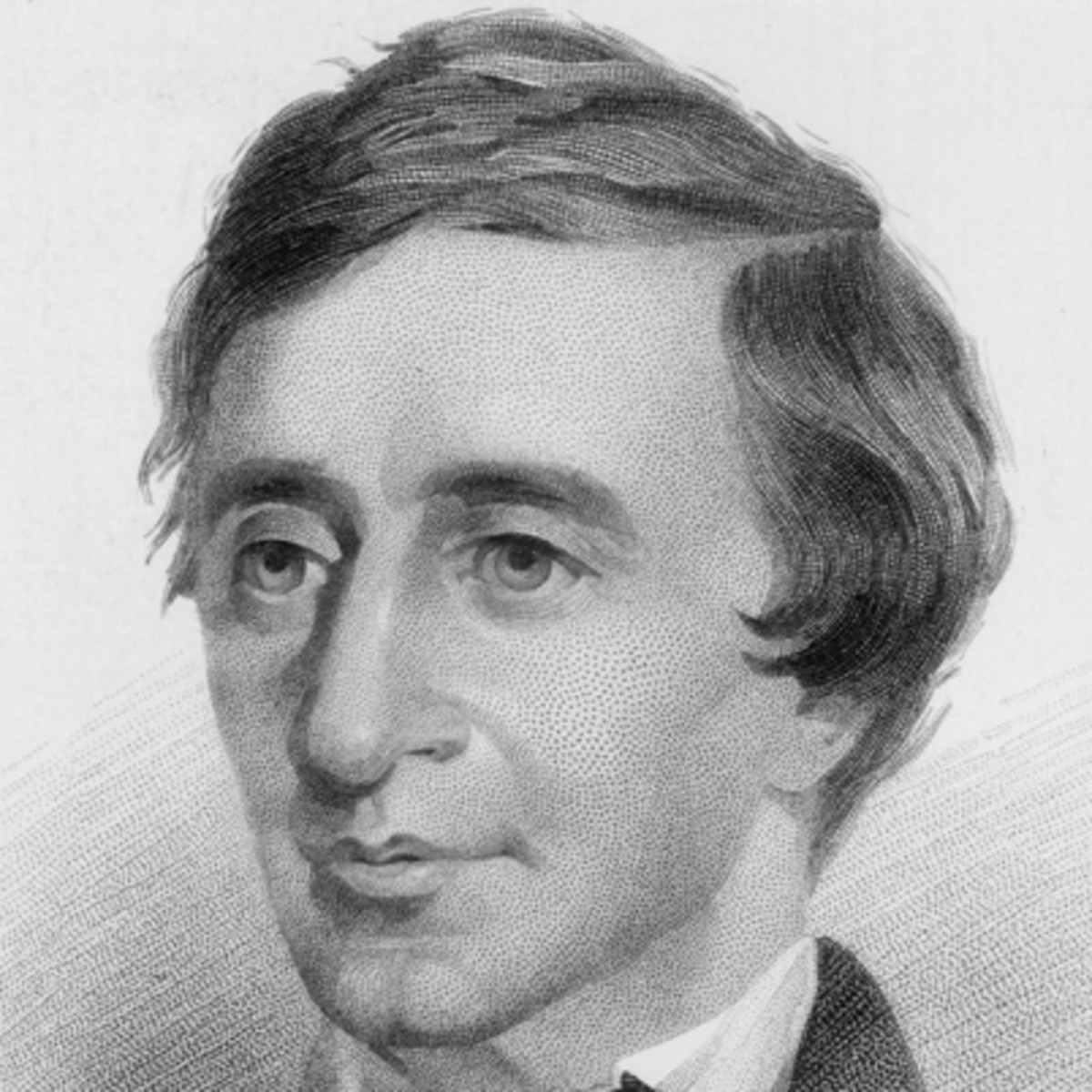

Henry David Thoreau

Biography

Henry David Thoreau, (born July 12, 1817, Concord, Massachusetts, U.S.—died May 6, 1862, Concord), American essayist, poet, and practical philosopher, renowned for having lived the doctrines of Transcendentalism as recorded in his masterwork, Walden (1854), and for having been a vigorous advocate of civil liberties, as evidenced in the essay “Civil Disobedience” (1849).

Early Life

Thoreau was born in 1817 in Concord, Massachusetts, the third child of a feckless small businessman named John Thoreau and his bustling wife, Cynthia Dunbar Thoreau. Though his family moved the following year, they returned in 1823. Even when he grew ambivalent about the village after reaching adulthood, he never grew ambivalent about its lovely setting of woodlands, streams, and meadows. In 1828 his parents sent him to Concord Academy, where he impressed his teachers and so was permitted to prepare for college. Upon graduating from the academy, he entered Harvard University in 1833. There he was a good student, but he was indifferent to the rank system and preferred to use the school library for his own purposes. Graduating in the middle ranks of the class of 1837, Thoreau searched for a teaching job and secured one at his old grammar school in Concord. He found that he was no disciplinarian and resigned after two shaky weeks, after which he worked for his father in the family pencil-making business. In June 1838 he started a small school with the help of his brother John. Despite its progressive nature, it lasted for three years, until John fell ill.

Ralph Waldo Emerson settled in Concord during Thoreau’s sophomore year at Harvard, and by the autumn of 1837 they were becoming friends. Emerson sensed in Thoreau a true disciple—that is, one with so much Emersonian self-reliance that he would still be his own man. Thoreau saw in Emerson a guide, a father, and a friend.

With his magnetism Emerson attracted others to Concord. Out of their heady speculations and affirmatives came New England Transcendentalism. In retrospect, it was one of the most significant literary movements of 19th-century America, with at least two authors of world stature, Thoreau and Emerson, to its credit. Essentially, it combined romanticism with reform. It celebrated the individual rather than the masses, emotion rather than reason, nature rather than man. Transcendentalism conceded that there were two ways of knowing, through the senses and through intuition, but asserted that intuition transcended tuition. Similarly, the movement acknowledged that matter and spirit both existed. It claimed, however, that the reality of spirit transcended the reality of matter. Transcendentalism strove for reform yet insisted that reform begin with the individual, not the group or organization.

Career

In Emerson’s company Thoreau’s hope of becoming a poet looked not only proper but feasible. Late in 1837, at Emerson’s suggestion, he began keeping a journal that covered thousands of pages before he scrawled the final entry two months before his death. He soon polished some of his old college essays and composed new and better ones as well. He wrote some poems—a good many, in fact—for several years. A canoe trip that he and his brother John took along the Concord and Merrimack rivers in 1839 confirmed in him the opinion that he ought not be a schoolmaster but a poet of nature.

As the 1840s began, Thoreau formally took up the profession of poet. Captained by Emerson, the Transcendentalists started a magazine, The Dial. Its inaugural issue, dated July 1840, carried Thoreau’s poem “Sympathy” and his essay on the Roman poet Aulus Persius Flaccus. The Dial published more of Thoreau’s poems and then, in July 1842, the first of his outdoor essays, “Natural History of Massachusetts.” Though disguised as a book review, it showed that a nature writer of distinction was in the making. Then followed more lyrics, and fine ones, such as “To the Maiden in the East,” and another nature essay, remarkably felicitous, “A Winter Walk.” The Dial ceased publication with the April 1844 issue, having published a richer variety of Thoreau’s writing than any other magazine ever would.

In 1840 Thoreau fell in love with and proposed marriage to an attractive visitor to Concord named Ellen Sewall. She accepted his proposal but then immediately broke off the engagement at the insistence of her parents. He remained a bachelor for life. During two periods, 1841–43 and 1847–48, he stayed mostly at the Emersons’ house. In spite of Emerson’s hospitality and friendship, however, Thoreau grew restless; his condition was accentuated by grief over the death of his brother John, who died of tetanus in January 1842 after cutting his finger. Later that year Thoreau became a tutor in the Staten Island household of Emerson’s brother, William, while trying to cultivate the New York literary market. Thoreau’s literary activities went indifferently, however, and the effort to conquer New York failed. Confirmed in his distaste for city life and disappointed by his lack of success, he returned to Concord in late 1843.

Move To Walden Pond

Back in Concord Thoreau rejoined his family’s business, making pencils and grinding graphite. By early 1845 he felt more restless than ever, until he decided to take up an idea of a Harvard classmate who had once built a waterside hut in which one could read and contemplate. In the spring Thoreau picked a spot by Walden Pond, a small glacial lake located 3 km (2 miles) south of Concord on land Emerson owned.

Early in the spring of 1845, Thoreau, then 27 years old, began to chop down tall pines with which to build the foundations of his home on the shores of Walden Pond. From the outset the move gave him profound satisfaction. Once settled, he restricted his diet for the most part to the fruits and vegetables he found growing wild and the beans he planted. When not busy weeding his bean rows and trying to protect them from hungry groundhogs or occupied with fishing, swimming, or rowing, he spent long hours observing and recording the local flora and fauna, reading, and writing A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849). He also made entries in his journals, which he later polished and included in Walden. Much time, too, was spent in meditation.

Later Life And Works

When Thoreau left Walden, he passed the peak of his career, and his life lost much of its illumination. Slowly his Transcendentalism drained away as he became a surveyor in order to support himself. He collected botanical specimens for himself and reptilian ones for Harvard, jotting down their descriptions in his journal. He established himself in his neighbourhood as a sound man with rod and transit, and he spent more of his time in the family business; after his father’s death he took it over entirely. Thoreau made excursions to the Maine woods, to Cape Cod, and to Canada, using his experiences on the trips as raw material for three series of magazine articles: “Ktaadn [sic] and the Maine Woods,” in The Union Magazine (1848); “Excursion to Canada,” in Putnam’s Monthly (1853); and “Cape Cod,” in Putnam’s (1855). These works present Thoreau’s zest for outdoor adventure and his appreciation of the natural environment that had for so long sustained his own spirit.

As Thoreau became less of a Transcendentalist, he became more of an activist—above all, a dedicated abolitionist. As much as anyone in Concord, he helped to speed fleeing slaves north on the Underground Railroad. He lectured and wrote against slavery; “Slavery in Massachusetts,” a lecture delivered in 1854, was his hardest indictment. In the abolitionist John Brown he found a father figure beside whom Emerson paled; the fiery old fanatic became his ideal. By now Thoreau was in poor health, and, when Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry failed and he was hanged, Thoreau suffered a psychic shock that probably hastened his own death. He died, apparently of tuberculosis, in 1862.