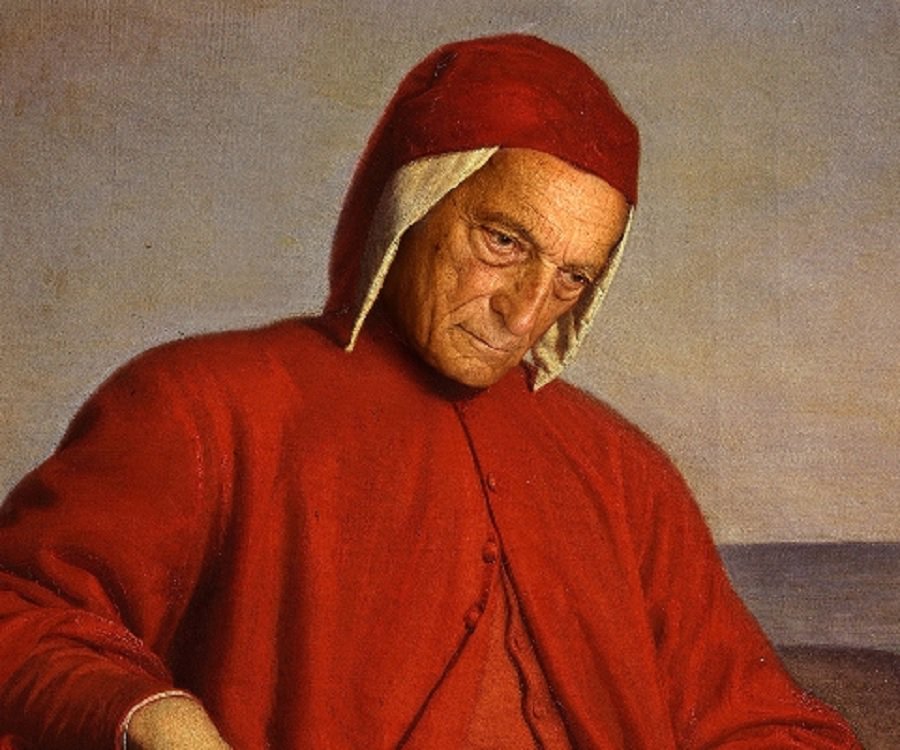

Dante Alighieri

Biography

Dante was an Italian poet and moral philosopher best known for the epic poem The Divine Comedy, which comprises sections representing the three tiers of the Christian afterlife: purgatory, heaven, and hell. This poem, a great work of medieval literature and considered the greatest work of literature composed in Italian, is a philosophical Christian vision of mankind’s eternal fate. Dante is seen as the father of modern Italian, and his works have flourished since before his 1321 death.

Early Life

Dante Alighieri was born in 1265 to a family with a history of involvement in the complex Florentine political scene, and this setting would become a feature in his Inferno years later. Dante’s mother died only a few years after his birth, and when Dante was around 12 years old, it was arranged that he would marry Gemma Donati, the daughter of a family friend. Around 1285, the pair married, but Dante was in love with another woman—Beatrice Portinari, who would be a huge influence on Dante and whose character would form the backbone of Dante’s Divine Comedy.

Dante met Beatrice when she was but nine years old, and he had apparently experienced love at first sight. The pair were acquainted for years, but Dante’s love for Beatrice was “courtly” (which could be called an expression of love and admiration, usually from afar) and unrequited. Beatrice died unexpectedly in 1290, and five years later Dante published Vita Nuova (The New Life), which details his tragic love for Beatrice. (Beyond being Dante’s first book of verse, The New Life is notable in that it was written in Italian, whereas most other works of the time appeared in Latin.)

Around the time of Beatrice’s death, Dante began to immerse himself in the study of philosophy and the machinations of the Florentine political scene. Florence was then was a tumultuous city, with factions representing the papacy and the empire continually at odds, and Dante held a number of important public posts. In 1302, however, he fell out of favor and was exiled for life by the leaders of the Black Guelphs (among them, Corso Donati, a distant relative of Dante’s wife), the political faction in power at the time and who were in league with Pope Boniface VIII. (The pope, as well as countless other figures from Florentine politics, finds a place in the hell that Dante creates in Inferno—and an extremely unpleasant one.) Dante may have been driven out of Florence, but this would be the beginning of his most productive artistic period.

Works

Dante’s Divine Comedy, a landmark in Italian literature and among the greatest works of all medieval European literature, is a profound Christian vision of humankind’s temporal and eternal destiny. On its most personal level, it draws on Dante’s own experience of exile from his native city of Florence. On its most comprehensive level, it may be read as an allegory, taking the form of a journey through hell, purgatory, and paradise. The poem amazes by its array of learning, its penetrating and comprehensive analysis of contemporary problems, and its inventiveness of language and imagery. By choosing to write his poem in the Italian vernacular rather than in Latin, Dante decisively influenced the course of literary development. (He primarily used the Tuscan dialect, which would become standard literary Italian, but his vivid vocabulary ranged widely over many dialects and languages.) Not only did he lend a voice to the emerging lay culture of his own country, but Italian became the literary language in western Europe for several centuries.

In addition to poetry Dante wrote important theoretical works ranging from discussions of rhetoric to moral philosophy and political thought. He was fully conversant with the classical tradition, drawing for his own purposes on such writers as Virgil, Cicero, and Boethius. But, most unusual for a layman, he also had an impressive command of the most recent scholastic philosophy and of theology. His learning and his personal involvement in the heated political controversies of his age led him to the composition of De monarchia, one of the major tracts of medieval political philosophy.